Most of the world’s great heroes started as a childhood dream. Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster dreamed of a baby rocketed to Earth from a doomed planet, gifted with powers beyond mortal man. Stan Lee and Jack Kirby dreamed of four bold adventurers changed by science to help humankind. And Emanuel P. Gill dreamed of three dead cops and a ripped pair of pantyhose. Welcome to the world of Westone Page.

Before we get going, a little historical context is required. For comic book readers in New York City, one store has always stood head-and-shoulders above the rest. Jim Hanley’s Universe was incorporated in 1985 in Staten Island and, fueled by its owner’s monomaniacal love of the art form, soon expanded to a choice Midtown location opposite the Empire State Building. In that massive store, you’d find all of the Marvel and DC you wanted, plus every other publisher under the sun. Hanley’s devoted a prominent shelf to local artists trying to get their work out there by self-publishing, and if you dug through it in the early 2000s you’d probably find a copy of Westone Page.

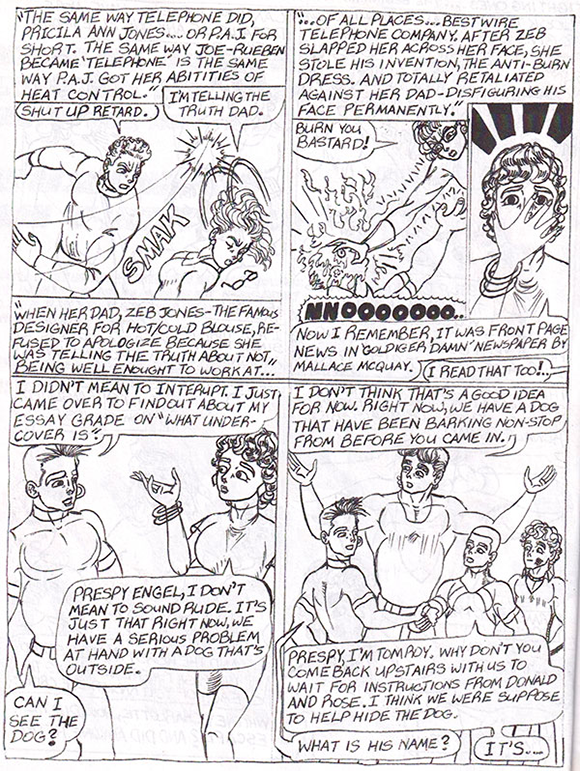

While most of the other minicomics on the shelf were artsy indie affairs, Gill was doing something different. His “E-Lectric Comics” imprint was a whole, fully-realized superhero universe with spin-off books and an ambitious release schedule. Sure, the actual publications were shoddily Xeroxed with content often being cut off at the page edge and covers that looked like they were colored with markers and left to sweat in a humid apartment, but the intent… the intent was powerful.

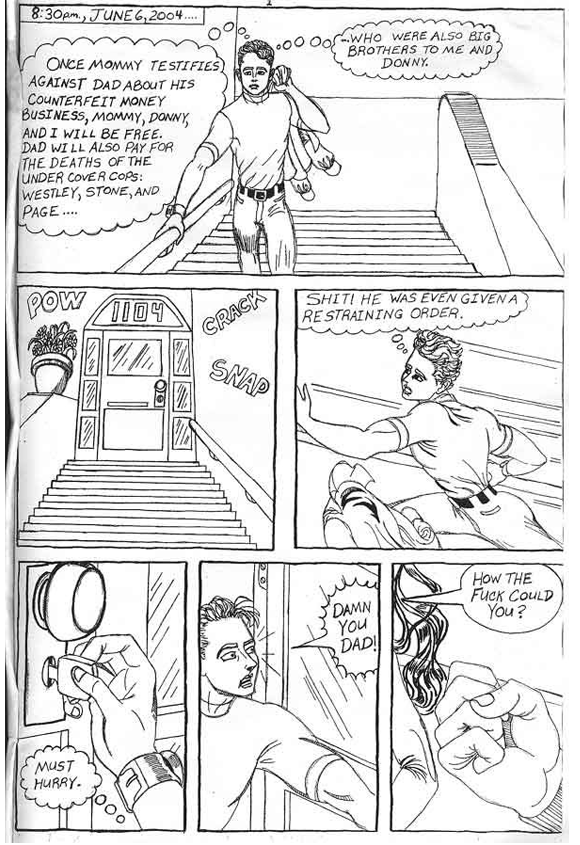

The flagship E-Lectric Comics title was Westone Page, which saw 7 issues published. The protagonist is a high school student named Crest Jones, whose father Jason runs a counterfeiting business. When Crest, his brother Donny, and their mother find out where their money comes from, Jason has the three undercover police officers assigned to guard the family – Westley, Stone and Page – murdered. Their life essences flowed into young Crest imbuing him with the wisdom and power of three police officers. This might seem to be a fairly minimal improvement, but nevertheless he adopted the unwieldy moniker of “Westone Page” and set out to bring his father to justice.

At first blush, this doesn’t seem all that unusual for an amateur superhero comic book. But the first blush is often the most deceptive. The basic structure of Westone Page is normal, but inside it is a seething chaos of deep weirdness, like a fish tank full of millipedes left on your ex-wife’s porch.

First off, we don’t actually see any of this dramatic origin happening – Westley, Stone and Page are nowhere to be found. That backstory is all communicated through Crest’s thought balloons on the first page of the first issue.

We eventually do get to see the trio of titular cops in a flashback in issue 5, but that comes in the middle of an interminable courtroom sequence. The vast majority of Westone Page consists of its characters monologuing to the camera about what they’re going to do to each other when they fight.

Emanuel is what we call in the industry an “idea guy,” more concerned with getting his cool concepts out there than weaving them together into any kind of coherent narrative. So every issue of Westone Page features a few pages of plot and the introduction of between seven and ten new characters, many of which are never seen again. The bad guys led by Jason all get half-pages where they do such things as make milkshakes and threaten to take their foes “to the back” – a unique verbal proposition that is deployed multiple times.

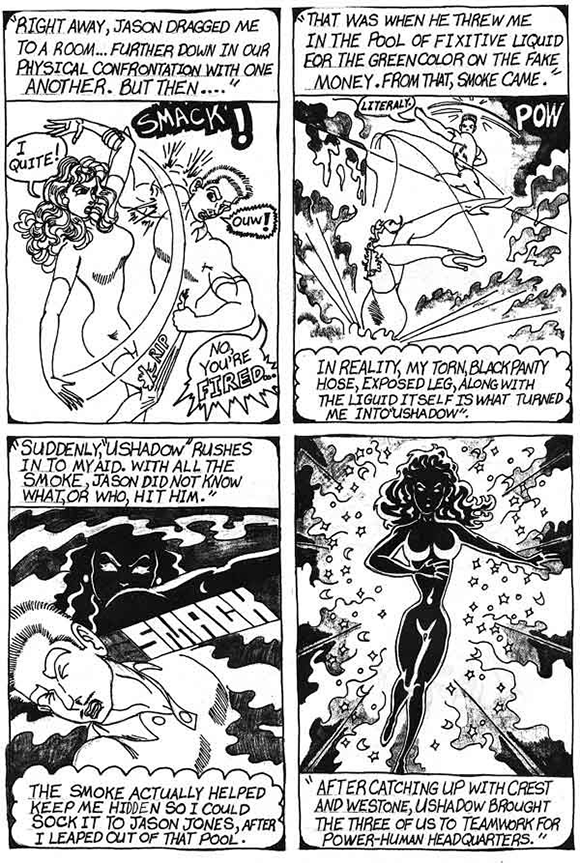

One of the most notable supporting characters is Westone’s superpowered girlfriend, U-Shadow. As Samantha McSullivan, she was a secretary for his father who discovered his counterfeiting business. They struggled, and he knocked her into a vat of chemicals that somehow interacted with her “torn, black panty hose, exposed leg” to transform her into a creature of coruscating energy.

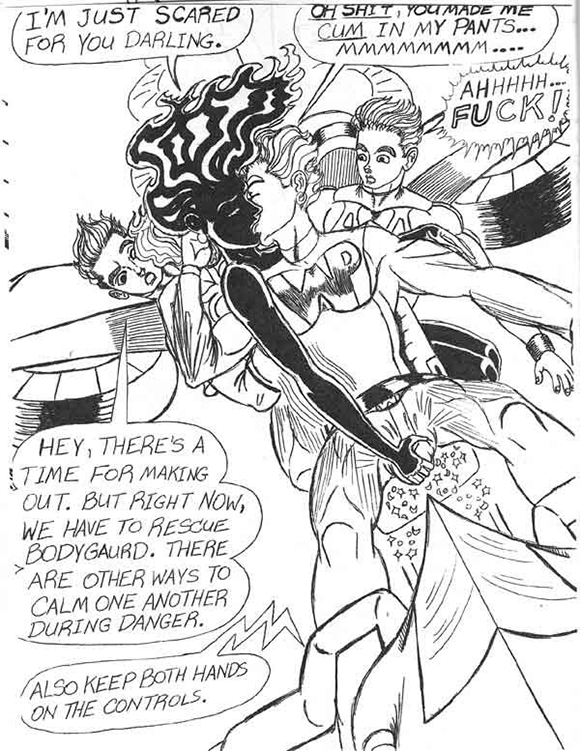

You’d rightfully assume from that sort of origin story that these comics are incredibly horny. And yes, while Emanuel stops short of showing full dong or penetration, E-Lectric’s heroes and villains are constantly sexing each other up. At one point, while Westone is flying some sort of jet-sled to confront the evil Dr. Master in “Empire Daddy City,” U-Shadow gives him a reacharound and makes him ejaculate in his pants. I can appreciate the desire to relieve some stress before a battle, but one would think having dried jizz on the inside of your super-leotard would get uncomfortable.

Gill is also a master of creative profanity. There’s a certain school of thought that the more cursing you put in a piece of content, the more mature it is. So Westone, his cohorts, and his foes all swear like sailors on nearly every page. The old favorites are mixed and combined, like the evil Jason Jones above referring to his estranged wife as a “shitbitch.”

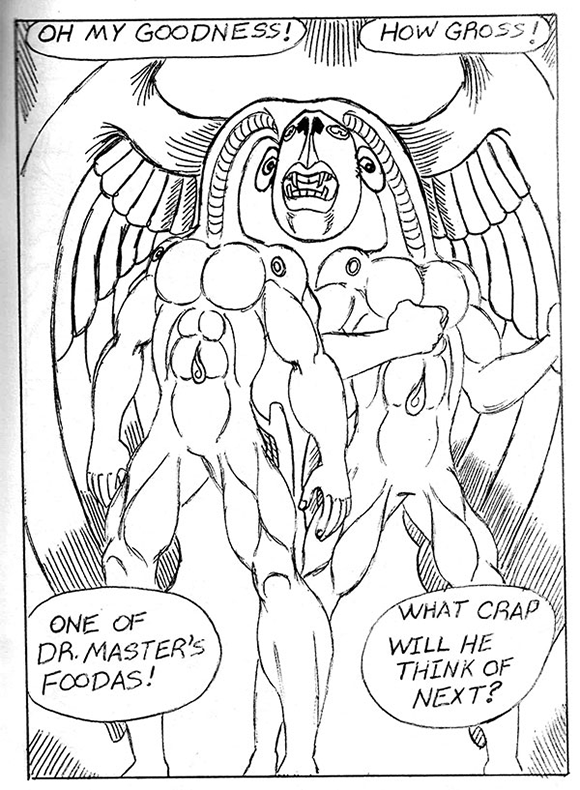

Throughout the run of Westone Page, we’re teased with our hero confronting his father. But the big climatic battle never seems to happen. Instead, the book detours into courtroom drama, with the judge, the prosecuting attorney and pretty much everybody observing turning out to be a superhero or villain. That’s interrupted by an attack from a new bad guy, the nefarious Dr. Master, who deploys bizarre monsters called “Foodas,” which have one head connected to two humanlike bodies with several suspiciously fuckable holes. Jason Jones escapes, never to be seen again.

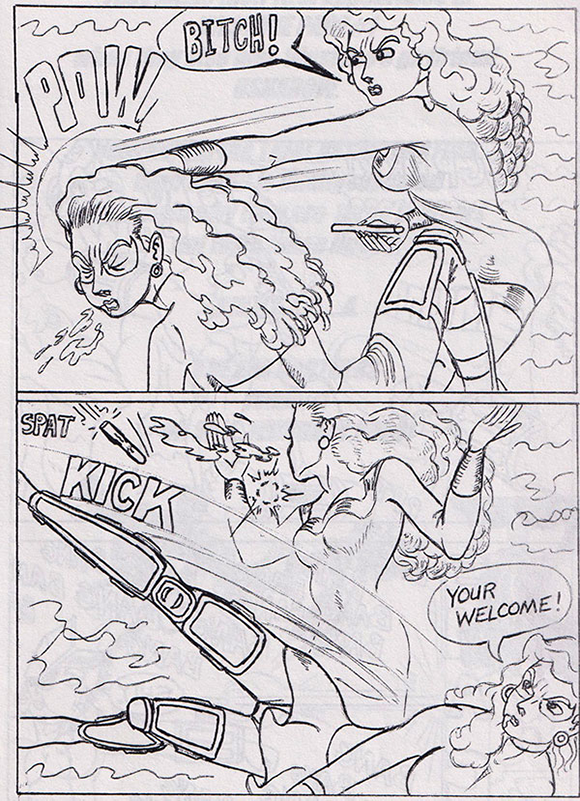

Additional titles followed. “The E.P.A. Brothers” followed a trio of siblings from New York as they kept their neighborhood safe. “Fighting Ones” was the obligatory team-up book, which paired Westone with a panoply of other “Power Humans” (and the dog Sniffer, the “Power Mammal”). “Ivory,” leader of the group Teamwork For Power Humans, also got one issue of a solo book that I’ve never seen a copy of. And in every issue, we meet at least a half dozen new characters like “Airbrush,” a villain who paints realistic doors on walls to make people run into them, or “Arthritis,” who has a wrist blaster that can make bones jiggly.

What’s fascinating about these books is how they’re obviously commercially motivated – in each issue, at least 1/3 of the page count is taken up with ads for E-Lectric Comics’ other offerings, often repeating the exact same ad multiple times in a single comic. Gill’s art style isn’t really congruent with the hot Marvel and DC artists of the era. Instead, his work hearkens back to Golden Age greats like C.C. Beck – figures are rounded and soft, compositions are static and fight scenes are simple and uninventive. They really seem like they were beamed into Jim Hanley’s Universe from a parallel dimension.

It’s hard to run down the genius of Emmanuel P. Gill. These comics are full of deeply hilarious moments, like when the Fighting Ones prevent a nuclear bomb from exploding by covering it with a large sheet of tinfoil. But everything is played with incredible seriousness. The common thread through almost every character is fathers – in addition to Crest’s abusive dad, nearly every other male parent presented in every one of his comics is a violent, abusive sociopath.

And, just as suddenly as E-Lectric Comics had appeared, they vanished. Gill stopped bringing his books into Jim Hanley’s Universe, and I’ve never met another comics shop owner in New York or anywhere else who ever saw or sold them. It looks like he set up an Etsy page a while back, but only the first two issues of Westone Page and some original artwork are available.

According to his Facebook page, he was also employed at New York’s storied Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2019, and even hung a drawing in the staff art show. But even more astonishing, he lists on his LinkedIn that he’s an art teacher at CUNY’s Lehman College in the Bronx, meaning the mind behind Westone Page is shaping young artists in his own image to create a new generation of pants-squirting, pantyhose-ripping Power Humans.