Well its kinda weird if you think about it that there was only ever one Halloween 1987. Ever! Now Im not tryin to pretend one year is objectionally better than another, i just personally happen to have a fondness for some more than others, due to nostalgia you see, and well, just think about that October. Lookin back on a summer of Robcop and Predator and Lethal Weapon and did you hear: the guy from Moonlighting is going to be in a action movie!? And then lets make it more specific and suggest that on this paticular halloween you happen to be a college student in LA. Oh yeah, Summer School was also 1987, so we know pretty much exactly what you might look like:

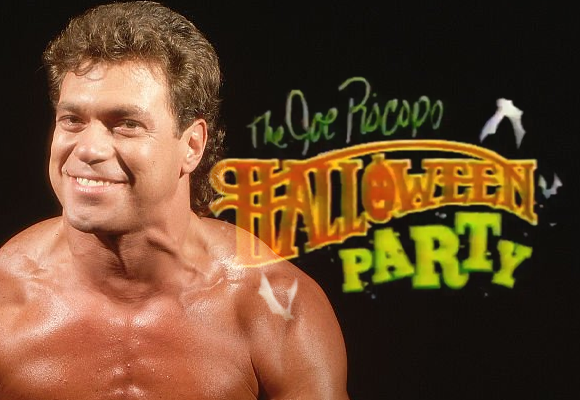

So your too old for trick or treats and maybe even costumes but that dont matter because your bud calls you on the dorm phone and says i got us two tickets to the hottest halloween party in town; that young new comedian everybody loves from Saturday Night Live and movies and who is becoming a superstar is coming to film his new special on Halloween Night right here at UCLA!

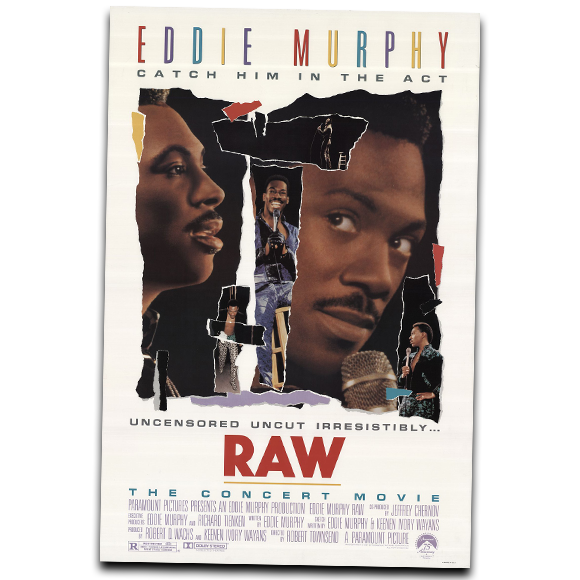

Haha no not THAT SNL superstar,

the OTHER one:

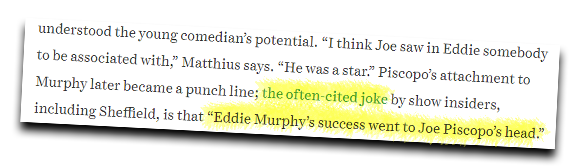

Yeah him. I honestly have no idea if I need to explain him or not to you, so real quick that’s Joe Piscopo, he was on SNL with Eddie Murphy right after the whole first group left or got fired and some people thought the show would end, but nope, it kept getting popular and Joe knew it was probably because of his killer Frank Sinatra impressions that saved the day.

So you can see why Joe had the showbiz juice that would make the shoulder-padded suits at HBO say: “Let’s give this man full creative freedom to do a Halloween comedy music show with a costume party for the students and we will broadcast it live to the homes of America.”

And thank goodness one of those homes had the prescience of mind to VHS record it and many years later post it for me and you and this guy to watch:

Joe wastes NO time in lettin us know what were in for. Maybe we were expecting just a hour of the best Jerry Lewis impersonation we ever seen in our lives but this aint that, he declares that we are in for some BAD BOY comedy by ridin out on the stage on a harley davidson motorcycle and wearin a harley davidson shirt that shows us his muscles AND sets off his hair real nice.

I believe that particular mullet variety is referred to as the Jersey Tidy.

He bellows a welcome to us and the crowd and then IMMEDIATELY suverts our expectations of what were in for by putting on a outfit that signals to us that we are about to see: some Rap Singing.

I been watchin this pretty closely and have come to the uncomfortable conclusion that he actually does seem to be scratching for real there. You may scoff and doubt at me about that right now, but I invite you to stay with me and see what you think when we finish up here today.

So Joe raps for second about how rap is so easy, you just say stuff! And then he does a on-stage costume change into WHITE BOY RAPPER

So a rough start, I know, for you and me, but the crowd responded with like ecclesiastical levels of ecstatic hollerin on this one.

You’ll maybe join me in the dilemma I had watching this one: It would be very bad if there were only white people in the live audience, but also any black people who were there could probly use a kind thought or prayer.

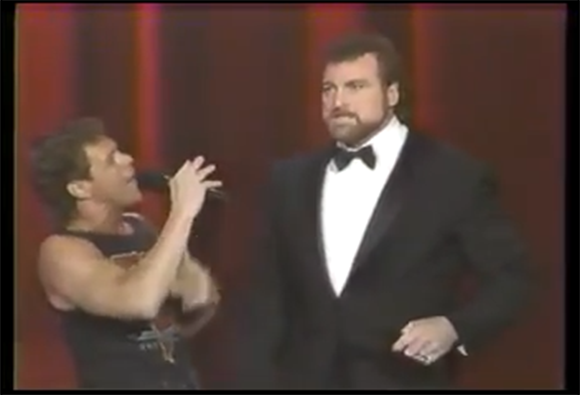

He finishes the rap sketch, makes a joke about UCLA parking tickets that KILLS, just as much for me at home as it did for the students, and then introduces John “The Tooz” Matuszak

(who for real I just learned played Sloth in Goonies, and who sadly would not live to see a 90s Halloween) The Tooz is on loan from the Raiders tonight to judge the costume contest, winner gets $1000, which back then was enough to buy about half a three wheeler! Let’s see our first contestants!

I thought haha thats funny, a person with their whole face covered up as a mummy is lip syncing, I wonder whos the 80s celebrity under there, I hope so much its Balki, but nope it was just a student dressed as a mummy.

I wish i could fully communicate the FRANTIC pace of this thing so far, Joe and and the kids and everybody seem kinda terrified about taking too much time on the live broadcast so everyone is just HUSTLIN.

Next they have some primo ‘87 high-cut and bethonged babes rush out and dance and the announcer yells please welcome to the stage WHAT HATH GOD ROTH to complete silence from the audience and then Joe comes out and shows us why doin impressions of singulurly physical performers like David Lee Roth is a bad idea.

Its like when your biology teacher would get a little loose on a friday afternoon and try out his Jim Carrey bits for the class. Hes a nice enough guy and its better than doin more pundit squares but lets not pretend its as good as the original.

Again, we are movin at a pace here somewhere between frenzied and panic. KEEP IT MOVING, I imagine the director yellin, WE ARE LIVE PEOPLE NEXT SET NEXT SET

Oh no. This is probably what you think it is, Joes doing a extended vocal impersanation of a black musician. Who he insists he has full respect for.

You can maybe see why at first I thought he was actually doing black- and possibly blind-face on this one but thats just a artifact of the poor recordin quality and Joe’s immence perspiration. Heres the thing though; if you watch that part, you’ll see that even though hes “just” doing the voice, that doesnt make it any better. He enlists a bandmate to join him, perhaps to provide some sort of cultural cover an counter-fire by showing us “See, even there laughin!”

Oh nope i guess i gave joe too much credit, its not even that, its just his white friend who is also real good at talkin like a black guy i guess.

If you listen close you can hear John Hughes screamin with laughter

But then here comes another curveball! That saxophone is not just a prop, Joe actually starts to play it!

With the same high-level enthusiasm and mid-level skill (ahem) he brought to the turntables, Joe makes that puppy wail, mournful and soulful such that we can clearly hear the intended message: “I AM NOT A CLOWN!” We draw a respectful veil over comedy for the moment, the show is now just two sensual sax buds tradin the most stanksome of jersey-flavored licks with each other.

Back to the costume contest: we get a skit with that ol’ halloween chestnut of one frat boy dressed up as Sherlock Holmes hitting another fratboy in the nuts with a hockey stick again and again and again.

Just inexplicable. Possibly brilliant in its moronery.

Joe returns, transformed in our eyes from when he played the sax so good. No cheap jester, he!

He does a Phil Donahue impression that is mostly wig and he interviews George Wallace dressed up as Oprah.

Every line Joe says is a fat joke. He does it 8 times.

Oof, this is getting a little rough, let’s take a little break from the special. Here, let’s rest our chemistry with this video of Joe hollerin a bob seger love song at his fiance who he met when she was 17 and his sons nanny and he was already married and makes her come out on stage and give him flowers and say she doesnt mind when they go on Howard Stern together and he pervs on her:

Okay breaks over, back to the special. The next costume contestants run out and sing their song and then a man dressed as a tongue comes out and licks them up.

Spoiler: they win.

And then we have a bit with two kids who are trick or treatin but when they knock on a door, its Joe Piscopo in a spittin image of Bruce Lee.

Again we all of us remember the david lee roth lesson. In this case its that Joe hasent yet learned that you have to be at least a little bit good at karate to be good at making fun of it. Hell aint that the way for pretty much anything? Anyway you can maybe see it comin that their gonna lean real hard into 80s Asian accent humor.

Im sure your brain is fillin in the blanks on how he says Halloween. The child actor is forced to say Tlick or Tleat my god for real what are we doin out here. I need another break, here lets watch Joe do the white boy rap at a recent Mike Lindell rally:

Okay another long saxophone thing from a special guy Joe flew all the way out from Atlantic City, and i dont know whats worse: if he thought the LA kids would actually like it or if this was his way of expressing California Hate-Spite as only a jerseyman can.

Then Joe and a lady that i think is supposed to be madonna come out and sing a song with no jokes. Just singing and dancing, but i guess hes supposed to be Dean Martin and thats all you need?

Still at a nicotine + cocaine speed, all of this. But then, all of a sudden, time slows. We enter a pre-recorded bit, shot in majestic black and white and moving at a stately pace.

Dignified.

We watch (and I guess the audience in UCLA did too on a screen or something?) while Joe once again transcends the bonds of base and vulgar comedy to show his breadth, depth, range, and reach of being able to play 4 different Robert DeNiros!

Uncanny.

Its so long, and totally ununcumbered by jokes. Joe seems to believe that his savant impersonation skills will carry our tired bodies for as long as needed, or perhaps this part was meant for Martin Scorsese’s eyes alone. Whatever’s going on, it just keeps going on.

We realize they were compressin the rest of the show so hard to make sure that this thing could be shown in its entirely.

It made me say a complicated prayer by the end, i could tell this part was finally about to end with as much nothing as it began, and just kinda the agony of it and thinking about all the unlaughin young faces there at UCLA realizin that they gave up the only 1987 Halloween they’d ever have? For this!? So help me, folks I found myself askin God: please, make it that Joe wrote a joke to end this…

A button, a crazy credit…

…anything to wrap this one up. Please.

Nothing. It feels like God did this to test how much i’d debase myself and abandon dignity in the face of despair, and I failed. I feel just like the end of 1984. Lets take another break with this old Joe Piscopo Miller Lite commercial.

Goddammit that was just the worst parts of the bruce lee thing again that wasn’t no break, fuck it i guess were just white knucklin through the rest of this one. Take each others hands and exchange reassurin nods were almost there.

The live show continues. Joe returns to the stage to accept the adulation of the audience about his cinema artistry and gives the fans what he knows they want, a lil live recap of what we just saw:

Its time for a finale and Joe has the consummant entertainers awareness of how to knock the socks off of these college kids with all the neon heat that only a live show in ‘87 could muster:

Yep, I probably don’t need to tell you but thats professor Tom Tomlinson playing focaccia and fuge on the world famous UCLA Royce Hall Pipe Organ!

You can tell he knows he has finally won the admiration and respect of the youth. But this aint your grammas phantom of the opera: In a move Andrew Lloyd Weber could only dream of, Joe Piscopo, renossance man, rises from the below the stage and joins Tom Tom to just EXECUTE on the rock and roll drum set!

Wildly, Joe pounds, he sizzles, he kicks, his grip on the sticks as firm and unyieldin as a step-fathers on your neck when you start to mouth off.

The rest of the band and professor tom valiantly strive to match and follow his, um, unconventional rythms.

Holy shit you guys, they fuckin did it, they came in at the hour, roll credits, high fives in the production booth, the costume kids and bikini babes and george wallace return to the stage as the crowd rises and roars at the spectacle recently beheld. But where’s Joe? Surely, he’s well-deserved restin among the laurels and panties bein hurled up on the stage in his honor, right? Hot Dog, if you believe that, I worry you havent been payin attention.

Back on the drums, sacrificing his body, emptyin his life essence out on this stage, this time with a Garth Brooks headset mic to make sure his voice is the loudest one singin Louie Louie. I was worried this would be where Joe blew up his big, tanned, veiny heart right there on the stage for the public, but he thoughtfully added a lil bumper at the end so I’d know that not only was he ok, he was still cool as hell.

Thank you Joe, thank you for what you did for them back then. I bet they never fully appreciated it, I hope I get to ask you about it one day. Well I did try to ask him, i got up real early and tried callin into his AM radio show he does for 4 hours every morning, but they told me Joe doesnt want to talk about old halloweens, this show is more for talking about the stuff fox news said to be mad about. I’ll keep tryin tho, I know the ol Joes still in there somewhere.

In the name of jesus christ amen.

This article was brought to you by our fine sponsor and Hot Dog Supreme: Haraka.