Explaining what I do here at 1-900 HOT DOG has proven difficult lately. Telling less online friends, prospective romantic partners, and cab drivers that I write about “uh, like old stuff? But funny. Like it’s weird, you know? Snailiens, haha. That one stupid Olympics mascot?” is getting tiresome. I’m pivoting: from now on, no more hemming or hawing. I’m a literary critic.

It sounds important. Not The New York Times Book Review important — the New York Review of Books important. But what work to discuss for my first column? I’ve recently read and enjoyed one new and one upcoming title from my Hot Dog colleagues, but I would hate to be accused of bias. (It’s about ethics in literary criticism.) Instead, I’ll consider Peachtree Carnivore, a text brought to my attention by esteemed community member Agent of Fortune. It is available exclusively in PDF format and doesn’t have a cover, but I’ve taken the liberty of creating one based on the image that graces the first page of the file.

Many of the great works of literature deploy narrative in service of a social argument. Madame Bovary rails against the romantic delusions of the bourgeoisie. Brave New World warns against a future where humanity is enslaved by means more insidious than punitive repression. And Ready Player One passionately urges us to never, ever forget Ghostbusters.

Peachtree Carnivore by Mark Mitchell is such a work. Its argument? That the all-meat diet which put Jordan Peterson into a coma is not only healthy, but indeed extends the human lifespan and transforms its adherents into erotic dynamos. Its author informs us that it is “not for the faint of heart.” Regretfully, it seems that he has fallen into the vogue of deploying “content warnings” for the overly sensitive modern reader. But perhaps this was merely a small concession to prevailing literary sensibilities. Onward.

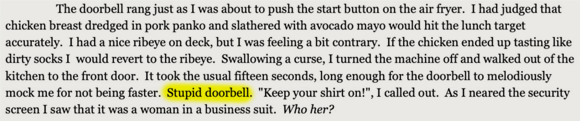

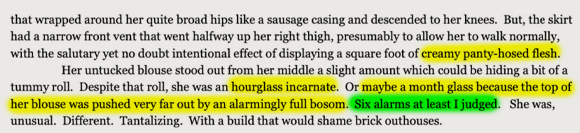

It is commonly supposed that whatsoever a character is doing the first time we meet them should tell us about what kind of person they are. Economy of storytelling, etc. When we meet Jack, the narrator of Peachtree Carnivore, he is doing two things: thinking about meat and analyzing the hips of a woman he’s just met vis-a-vis their birthing capabilities.

Boy meets girl. A timeless foundation of fiction. Boy is Jack Mason — sixty-something, unemployed, living off the inheritance provided by his abruptly deceased parents. Girl is Gladys Clayton, personal assistant to Jack’s dear friend and ethical billionaire Sam Grayson. Sam has sent Gladys to retrieve a book from Jack, but their introductions quickly take a turn for the libidinous.

Lest you think that our protagonist is motivated solely by the carnal pursuits, Mitchell is quick to point out that he is rather brainy as well.

And neither is he the sort of jobless senior citizen who is attracted solely to women forty-five years his junior. No, he can appreciate the beauty of a woman merely twenty years younger than him, especially one who herself cannot discern her charms for herself.

But what of the book? A Shakespeare first folio, which you may recognize as being doubly superlative — the rarest edition of a work by the most famous author in the English language. Note how Mitchell contrasts the high-brow context of the Bard with the bawdy actions of his characters, perhaps a commentary on the transformation of Shakespeare from ribald popular entertainment in his own time to dreaded, stuffy high school text in ours.

Needless to say, these two lovers find themselves tumbling into one another’s arms. Of course, sexual congress is famously difficult to write. What is erotic to the author may be repulsive to the reader. Mitchell slices this Gordian Knot by handwaving most of the actual acts themselves, preferring to describe the preliminaries and post-scripts.

Note the use of the term “gob.” An unusual choice in such a scene, to be sure. Slang for the mouth, it is typically used in gustatory — rather than amorous — contexts. But Mitchell repeatedly deploys it here. “Gorgeous gob,” “exquisite gob,” and so on. Grotesque? Parody? Or a sly elision of consumption and consummation?

It certainly did! And with the oral examination complete, Jack and Gladys move on to the main course. Gladys was, of course, a virgin up until this encounter. And now, the two are deliriously in love.

They decide to marry immediately as they are both of the conservative, traditional persuasion.

But first, Jack offers to coach Gladys on moving away from the SAD (Standard American Diet) and embracing the carnivore lifestyle which has granted him vitality atypical of his advanced age.

Jack’s carnivore diet is responsible for not just his youthful looks and healthy physique, but a clean-smelling breath and fine-tasting emissions.

As the couple feverishly makes plans for their future, Mitchell provides an early twist: this apparently chance meeting was in fact engineered by Sam, Gladys’s employer and Jack’s closest friend. Jack informs Sam and his wife Clara that he and Gladys intend to wed, being staunch moral traditionalists who have known each other for less than twelve hours and have already had intimate relations out of wedlock.

Many a male author stumbles when approaching the task of writing female characters who are believable, multi-dimensional human beings. Mitchell, thankfully, accomplishes this with gusto. Consider this passage, in which Clara and Gladys discuss the latter’s upcoming nuptials.

Note also Mitchell’s unconventional use of the characters’ names at the beginning of each line of dialogue. A mark of a literary nonconformist, as is his alternation — seemingly without rhyme or rhythm — between present and past tenses.

Unrealistic? Absurd? Contemptuous? Certainly the woke literary establishment would have you believe as much. But consider that in addition to her voracious hunger for seminal fluids, Gladys has another, quite intellectual hunger.

Yes, Gladys is a magnificent speed reader. So-called “scientists” may be skeptical of claims of reading more than 1,000 words per minute, but said scientists also believe that a diet consisting solely of meat and eggs is “unhealthy,” rather than inspiring the kind of sexual power that most men can only dream of.

Jack has interests beyond boluses, however. He quickly introduces his wife-to-be to his suitably impressive home stereo setup.

No buffering! Jack is a man of means. And broad taste, besides.

No divas, boy bands, or rap. Uncharitable readers might detect something of a commonality between two of those three genres, but recall that Jack is a conservative thinker. It’s modernity he despises, not any particular racial group. And while he’s certainly had detailed sexual thoughts about his best friend’s wife, he finds the notion that she might want to bed him quite surprising.

Yet at their wedding, Gladys proves to be somewhat less traditional than she initially made herself out to be.

Then again, Clara isn’t the only woman Gladys embraces in such a manner:

Is it “untraditional” for a man to analyze the cup size of his new wife’s mother? Is it “not conservative” for a woman to kiss her elderly mother on the lips? Mitchell ironically juxtaposes these scenarios with his characters’ disgust towards degenerate, craven wokeness. But they live in a world ruled by the socialist agenda, which at some point in the past made multiple marriage legal.

Jack demurs. He’s attracted to Clara, no doubt, but demonstrates the courage of his convictions in his reluctance to act on those feelings. The law does not determine what is just.

And yet.

Less than an hour later, Jack is achieving simultaneous (heterosexual) climax with his best friend. How to explain this apparent reversal? Stranger things have happened in reality. Is it not unfair to expect fiction to follow staid, predictable character arcs? In day-to-day life, people make irrational decisions which run contrary to their stated beliefs all the time. And let it not be said that anyone in this erotic configuration is homosexual.

The two couples fall into a sort of double marriage. And while Jack may study the precise length and girth of Sam’s phallus, muse on the shape of his body, and plunge his own member into the depths of his wife only moments after his companion has reached climax inside of her, he is emphatically heterosexual.

Jack meets Gladys’s parents and explains his carnivorous lifestyle to them.

He assures Gladys’s parents that she is in good hands. Jack has more money than he knows what to do with, looks forty thirty five, and knows a great deal about dietary science.

Convinced by his extolling of the benefits of the carnivore diet, Glenn and Martha gradually take it up and find that their health improves rapidly. The family is also able to move Glenn’s eighty-something-year-old father, Carl, into a private nursing home which is amenable to Jack’s special diet. Previously suffering from cognitive decline, he begins to make a miraculous recovery as a result of ditching carbohydrates.

If Jack had an easy time communicating the benefits of the all-animal lifestyle, it is another thing altogether to explain his marital arrangements. Clara assists by explaining that what seems like leftist moral dissolution is, in fact, a deeply traditional and conservative arrangement.

Martha is intrigued — recall that she herself is a kisser.

A fair objection from Gladys, who draws the line in their sexual experimentation at voyeuristic incest. But passion knows no boundaries regardless of what the leftist world government might try to impose on us, and Martha is overcome by Clara’s discourse on her deepest desires in this life — being penetrated constantly by whichever penis happens to be on hand and having babies until she is no longer physically capable of doing so.

Mitchell knows women. It isn’t “DEI” to admit this, but this is what we’re actually like! We have to pretend otherwise due to the pernicious efforts of feminism, but deep down, all women are secret bisexuals whose fondest wish is to break records for most offspring produced by a nymphomaniac carnivore.

The introduction of Gladys’s parents into their orgiastic home life complicates matters somewhat, but not too much.

And recall that Jack is a conservative man who despises the “gender lunacy” and “social idiocy” of our deeply progressive moment.

But a hero does not balk at a challenge. Did the hero of Atlas Shrugged, Atlas, back down when confronted with the difficulty of hefting up the earth over his head? No. And neither does Jack, plunging — if you’ll pardon the pun — ahead into greatness. And in her own way, Gladys does as well.

Characters overcoming trials is one of the cornerstones of fiction. Here, Gladys overcomes her resistance to having conjugal relations with her biological mother, while her biological father muses on the same with her. Should we recoil in disgust? Accuse Mitchell of unbelievable characterization? No. We should recognize that these characters are so so empowered by their rejection of the dictates of the criminal gangster FDA that they have become fully self-actualized, able to transcend the petty taboos progressivism imposes against fucking your parents.

Peachtree Carnivore continues on past this climax to detail the addition of two final members to the Mason-Clayton sextuplet. First, Jack entices his family doctor to join them with a direct proposal.

The last member — and I use that term in both senses — is perhaps the most surprising of all.

Our eight partially blood-related lovers spend their years, we are told, producing a bounteous wealth of offspring, including some which are no doubt the product of congress between Gladys and her father, or between Gladys and her father’s father.

But readers of Peachtree Carnivore will recognize that I have conspicuously omitted something of great importance from my review up until this point. That something is, of course, the automobile — which is the subject, by my estimate, of roughly a quarter of the book.

It is tempting to dismiss the great deal of Peachtree Carnivore given over to the discussion of cars and the customization thereof as a weakness of the work, a diversion from the core thrust of the text. In fact, the inclusion of this theme echoes that of carnivorous consumption and sexual licentiousness. For what is the car but a glorious extension of the body? And what is fuel but the meat of the car? Electric cars, it should go without saying, are equivalent to those Americans who consume plants — tools of the woke.

Lastly, I must attend to one objection that the reader may have mentally raised during this review. “Surely,” I hear you contend, “this is a work of parody, for it neither titillates nor makes a compelling argument for an all-meat diet.” First: you are a craven swine. Perhaps if you hadn’t deadened your mental faculties with carbohydrates, you would be able to appreciate Mitchell’s passionate plea to create a world of meat-fuelled incest monsters. Second, if this is a “bit”, to use the vernacular, then he’s been at it for at least seven years.

That’s right: Mark Mitchell has been an adherent of the carnivore diet for at least seven years. And if he’s seen the health benefits of such a lifestyle, then I can only assume that like his protagonist, he’s also become an impossibly wealthy, pussy-crushing ubermensch rather than a lonely old man writing 9 Chickweed Lane fanfiction on his Blogspot. I salute him and his dozens of beef-powered children.

This article was brought to you by our fine sponsor and Hot Dog Supreme: DeltaFoxTrot, who would thank you very much for not besmirching the good name of their Amos/Alistair fanfiction.